I never noticed columns on buildings the way I do now before I moved to Alabama. They are everywhere. During trips to the beach, I see them on everything from community college campuses to Publix. Last week, while at the beach, I even saw them in Big Fish, a restaurant in a strip shopping center (I had outstanding Scottish salmon prepared "Big-Fish" style;my husband had yummy crabcakes).

|

| Big Fish, an Orange Beach, Alabama, restaurant. |

I am reminded of what Gunther Barth has to say about how architecture fits into the efforts of human beings to create visual harmony. And whether on Gothic, Neo-Gothic or Greek Revival-styled buildings on college campus buildings or elsewhere, pillars seem to represent something huge literally and figuratively. Regarding the latter, they represent how people look to the past as inspiration for their aspirations. This was definitely true during emerging urban life in antebellum America.

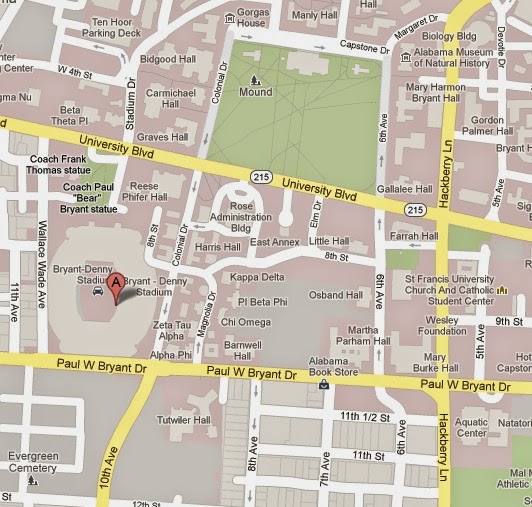

The idea of space in emerging urban life is one of the topics I will address this fall with students enrolled in this course. In the meantime, I will keep thinking it all over as I keep getting to know the campus and, indeed, Tuscaloosa. I have been here for more than two years, but am still learning my way around. The numbered grid streets are helpful.

.JPG)